ARMANDO VERDIGLIONE INTERVIEWS FERDINANDO AMBROSINO

You were born in Bacoli.

Yes, a little Phlegraean town in the province of Naples.

What year?

Back in 1938. I'm now sixty-four years old. But, thank God, I feel as fit as a fiddle, to go on creating for a good deal more years yet.

The new season is beginning. Were your parents from Bacoli too?

My parents were from Bacoli and my grandparents from Procida. In fact, the surname Ambrosino comes from the island of Procida. A beautiful island.

What about on your mother's side?

My mother's parents came from Salerno.

From Campania too, anyway. In 1938, though, Bacoli was smaller than today, at least in population.

It was a very small village. Bacoli became a borough in its own right in 1917.

It's in the Gulf of Pozzuoli.

It faces onto the Gulf of Pozzuoli. My studio is right in front of the Gulf. Before, Bacoli was a hamlet of Pozzuoli. Today, it is a small town of thirty thousand inhabitants, with its problems in the summer, because it looks out onto the sea, it has nice beaches and so attracts a lot of commuters from Naples.

It has an ancient history, too.

Yes, very ancient. Wherever you dig in Bacoli, there are works from Roman times. Some have been enhanced, others destroyed over time, but the most beautiful pieces can be admired.

Other things appeared when the city of Naples was the metropolis of the planet, five hundred years ago roughly.

Bacoli also lies on the territory of Cuma. And Cuma represents a focal point in Roman and ancient culture. The first Greeks landed in Cuma. And there is a magical presence: the Sibyl's cave. I don't know if I told you, but I took some photographs inside the cave. We took my paintings there.

Yes. They're black and white photos, very effective.

There's a particular magic.

Was it your grandfather or your father who moved from Procida?

My grandfather.

Was he a sailor?

No, he was from the countryside. He loved the countryside. In fact, he made good wine. He produced Falanghina, Piedirosso and Aglianico wines. He enjoyed his food and wine. As his cellar was near the beach, where the fishermen pulled in their nets, he would offer them a drink, which he drew on tap from the barrel.

While they had fresh fish. Your maternal grandfather, on the other hand, came from Salerno and had settled there.

He had been an emigré, one of the first, at the beginning of the century. He went to live in the United States, where he stayed for many years. My father went to the States too.

Did your father emigrate in the Twenties?

Yes, straight after the war. He spent a long time, ten years, without ever coming back.

What about your maternal grandfather, who had been there at the beginning of the century...

...he came back long after my father. He stayed there for thirty years, without ever wanting to take his family. He came and went, he had children then went back to America. He didn't want to move there with his family.

He didn't want to move there, he wanted to return.

He spent a long time there, though.

Whoever comes to Bacoli can go all over the planet, even to the United States, but then comes back to Bacoli. Is that right?

It's an attraction. It's a place that fascinates people. My father stayed in the United States for ten years. When he returned, still young at forty, he married my mother, who was twenty.

What about brothers and sisters — how many do you have?

We are three brothers. One followed in our father's footsteps: at twenty-two, after his military service, he left for Venezuela. At that time, people generally preferred South America, because it had a lot to offer.

That was after the war.

In 1952, not immediately after the war.

In the Fifties, it was Argentina, Venezuela, then Canada or Australia. Not the United States, as in the first and second decades of the century.

In Caracas my brother did very well. He became an industrialist. Now Venezuela is not a great nation any more. It's going through a very particular period.

[...]

What about your other brother?

My other brother has always lived in Bacoli [...] he was a public service employee, in the Inland Revenue office of Naples, for thirty years. Now he's retired, he's a grandfather, and he's happy with that.

Of course, he upholds values too, in a different way; he has travelled inside, others have travelled outside. And he's had his experiences, even staying in Campania.

Each person has their own way of being and of seeing. He has his own wishes and ambitions. He's not very fond of travelling, around the world or around Italy. So he's a quiet fellow. I and my other brother from Caracas are more adventurous, we like visiting towns and cities, going round the world. I particularly like visiting and getting to know places.

Well, your whole work is a voyage.

Definitely, a voyage.

While keeping this base in Bacoli, though.

The base of the voyage is Bacoli. My artistic route starts from Bacoli.

[...]

So you are the third son. While the first son travels, goes to the United States, and the second follows tradition, becomes a public service employee and remains in his land, the third does neither one or other of those things. Or rather, in a way, he does both, he travels and he upholds values, re-inventing them.

I was tempted many times, when I was twenty, to move to the United States. I didn't do it in the way my brother and my father did, but in a different way, going to the States often.

You often go to the States because there was the account of your maternal grandfather and of your father. The United States were already in the account when you were a child.

The United States and New York have stayed in my memory, all the things my father recounted to me, all his adventures, how hard he worked, many things. I did not move to the States. But it's as if I had. Then I did go. I began an artistic itinerary too. I've had various exhibitions.

[...]

So you were born in 1938; then there was the war, for five years.

I was very small. My memories are very blurred. In 1943, the war was over in the south [of Italy].

So, at five years old, only a few, very blurred pictures remain.

Then, after 1943, in 1944 and 1945 you began primary school, and in the Fifties middle school and then high school with classical studies. Was that in Bacoli or in Naples?

No, there weren't any middle schools in Bacoli then. I went to middle school and high school in Pozzuoli.

It was the main centre.

Today it's a town with a hundred thousand inhabitants. And it's still an important centre in the Phlegraean area.

At middle school and high school drawing was compulsory.

Yes, but I never did any. The fact that the teacher made us draw put me off completely.

Because it was according to certain patterns, certain rules, projections...

And so I didn't draw. So the teacher was convinced I couldn't draw. But at the end of the last year of middle school, he said: “Do a drawing of your own choice”, and I improvised what I had in mind, doing it with a real desire to draw. When the teacher saw it, he didn't believe I'd done it myself and said: “Who did it for you? Then you can draw!” “Of course I can”, I answered. “Well then why have you done nothing for the whole year?” he asked me. So I said, “Because you said to draw a bottle, and I wanted to do a landscape”. So, in my last year of middle school, I began to paint and draw.

But I'll tell you how my passion for drawing and painting began. There was a painter in Bacoli, a good artist, who followed an old tradition of painting. I used to meet him sometimes in the street. He was a genuine artist, because he interpreted the true in a wonderful way. He would open his box and sit there for two hours, painting. My friends would walk away after ten minutes, but I would stay and watch him. The box, the paints on the palette used to get me very excited, like when they used to let us choose a chocolate, as children.

Were you at primary school or middle school?

I was in the first year of middle school, I might have been twelve or thirteen.

What was the painter's name?

Gennaro Massa, a local teacher who painted beautiful things. His colours used to excite me, and I realised then that my passion for painting was strong. So I began doodling.

[...]

While the teacher at middle school and then high school was only a technician, he wasn't an artist. What did you do after high school?

I enrolled at the University of Naples, at the faculty of geological sciences. I had almost finished the course, I only had two or three more exams to sit. But I didn't want to wait, I thought I would be too late, I absolutely had to devote myself to painting. So I dropped out of university.

In fact, Dino Buzzati calls you “young Neapolitan geologist” in his text. That's in 1969.

I was twenty-four, when I left university to devote myself exclusively to art, to painting. At that time, my ambition was to paint, to paint and nothing else, and fulfill everything I wanted through painting. I wanted to derive everything from painting, to make a passion into a reason for work.

I wonder about the geology, too.

Why I chose geology? Because I didn't really believe I could study the sciences in a highly rational way. So I tried to find a faculty that gave some sort of freedom for personal interpretation too. I was convinced that, in geology and in the study of the earth, not everything was perfectly and scientifically explained, that there was intuition and research. I thought that faculty might suit me better somehow [...], would suit my way of seeing things more. I had started painting in a big way and was sticking at it. I was devoting more time to painting than to studying.

From the first year?

I painted a lot even at high school. I had started holding exhibitions and had received approval from some critics like Paolo Ricci, in Naples. Even when I was sixteen or seventeen, he had written some very positive remarks about my painting, also because I took on very large canvases. Ricci saw a great desire to express myself through painting, and wrote some very encouraging remarks in [the newspaper] “Unità”, in 1955 I think. So I had already had some approval. And so I thought: why waste time doing other things I don't believe in and that I shall never finish? That's how I decided to dedicate myself solely to painting. I began my itinerary from there.

Did you meet other artists, later on, any maestro?

Yes, I think the basic turning point, especially for making me understand the art that existed in the world, not only in the province of Naples, was the presence of a maestro, Guido Tatafiore, Professor at the Academy of Naples. He was a likeable person, a highly intelligent man and, above all, a great artist [...] It was an extremely important meeting.

By chance...

... by chance, but very important. He was a very generous person, a true artist. Above all he was an avant-garde artist. He was one of the promulgators of abstract art in Naples in 1955. He made me and a few other young people see that painting is not just representing things.

[...]

So, after Gennaro Massa, he was your real maestro, the one who gave you technique.

Yes, he opened my eyes to painting.

And that's no small thing, the palette, with the paints. But your travels began as early as the Sixties.

In the Sixties I began travelling around the different museums of Italy.

Well, in Naples itself there is the Capodimonte Museum.

But also the museums of Milan, Rome, the Gallery of Modern Art; I began to follow the exhibitions taking place in Italy.

Did you meet any other artist?

Of course, many from that time, in Milan.

Anyone in particular?

No, not in particular. Mostly occasional meetings. I began my artistic itinerary holding exhibitions and taking part in competitions. When I had my first exhibition at the Maschio Angioino in Naples in 1967, I was afraid of presenting myself to the public. I had done a fine group of works. A Neapolitan sculptor, Luigi Ciccone, saw them. He was president of UCAI (Union of Italian Catholic Artists), whose headquarters were inside the Maschio Angioino. “Why don't you hold an exhibition, they're fantastic”, he said. He grew very fond of this expressionist painting of mine. Although I painted the Phlegraean landscape, the works were full of pathos and had been executed in a very gestural way. On that occasion the critic and art historian Piero Girace discovered me. He wrote in [the newspaper] “Roma” and was a friend of many Italian artists, a friend of De Chirico and of Guttuso. When he saw the exhibition he was enthusiastic about it and brought me into a group he had formed, “Tradition and Reality”. [...]

Naples, Caracas, Milan. Then came the Seventies.

And other exhibitions. Meanwhile, in Caracas I had a two-yearly date. Every two years I repeated the exhibitions. In all I had ten solo exhibitions in Caracas.

[...]

Coming to a more recent period: there was the Palazzo dei Diamanti in Ferrara, San Michele a Ripa in Rome, then San Marino.

In the Republic of San Marino I also won a prize. Then Lecco, Bergamo, Foggia, Catania.

And then we organized the exhibition in Paris.

The big exhibition at the Paris Art Center, and the other one we did together in Rome, at San Michele a Ripa. That was a great exhibition!

Definitely. Then Antibes.

At the museum of Antibes.

And in Geneva.

Yes, a good exhibition in Geneva too. Then, in 1994, there was also more direct contact with New York [...] in 1994 I was invited by a New York gallery in Soho to the Spazio Italia Gallery [...] It was an important exhibition because it opened up the American market for me. Then we repeated it in 1997, in the same gallery again, once more with great success.

[...]

Are there many Italians?

Italians passing through, maybe, and many who live there. Since 1998, I've been working with this gallery in San Francisco, with excellent results.

So, as far as your voyage and artistic itinerary are concerned, there was an abstract and slightly non-representational phase.

Yes, despite being a figurative painter, greatly influenced by the Phlegraean landscape and the landscape of Campania for thirty years, I have interpreted the landscape according to my vision. [...] I observed and saw things in a light always charged with events.

Hyperimpressionist.

Hyperimpressionist and also expressionist, gestural, very strong. At that time my works were regarded with diffidence by the public in Campania, which was still tied to a very figurative, very conventional pictorial tradition of the early twentieth century.

There was something specific in your work. There was always abstraction.

Definitely, the Cubist lesson had not been lost. It was still there.

There was always a process of abstraction.

That period is still very significant in my painting, because of this Phlegraean landscape, painted with Expressionist and Cubist influences, but with a particular authenticity of mine, a vision of things that was my own. Today it's still a significant period. And so, I continued with it for many years.The turning-point came between 1988 and 1990, and you have seen this progression: the Cubist way had allowed me to do things according to volumes; then, in the Nineties, those volumes dissolved, so there was almost a return to postimpressionism. Form dissolved. It was a very significant transformation, because as it dissolved, form...

... it appeared to dissolve.

... the Cubist form appeared to dissolve. With postimpressionism, we seemed to be taking a step backwards, but that's not actually what happened. From then onwards, people looked at things in a completely different way.

[...]

At the same time, yours is not the non-representational of the Fifties, which was seen in Italy. You did not adhere to pop art in the Sixties. Nor did you take part in conceptualism in the Seventies, nor in the flow of the Eighties and still less in the New Age of the Nineties.

Let's say I was out of time.

You have rigorously followed the specific quality of your itinerary.

With the experience I acquired, and the professionalism, if I'd really set my mind to it, I could have been one of the avant-garde painters, doing the things others were doing. But I chose to paint for enjoyment. For pleasure. There's no pleasure if you don't do what you feel. I did what my feelings prompted me to do. And perhaps, sometimes, I've been penalized, because I've been left out of the big trend exhibitions. Unfortunately, a price has to be paid. But today I believe I am a painter who paints according to an originality of his own.

Absolutely. What I notice is your constancy. [...] It is always a process of abstraction, it is always the landscape of Bacoli, which arrives at writing. More and more a writing. And there is no break, in these phases. On the contrary, I notice the constancy. There isn't a big distance between the structure of your latest icons and your works of the Fifties.

Quite the reverse, I've made this comparison myself and many other people are making it too. Between my works of the Seventies and those of today, it's a very short step.

And those of the Fifties.

Yes, of the Fifties too. There have probably been influences of various nature, over the years...

[...]

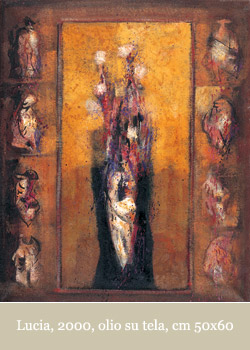

What is the icon? It is painting as writing, because Naples is a great civilization. Neither the American avant-garde nor the European avant-garde can consider themselves the source of it. There is a great civilization, which is that of Naples: it's a question of accepting this bet by contributing to that civilization, it's a question of taking it and going beyond, presenting it, again, in another way. There is also a reading of Naples, through the icon, but when I say Naples, I mean Campania.

My icons start out from Campania, from the Phlegraean area, from Cuma. But I think they deal with problems and atmospheres that can be found everywhere in the world.

[...]

The icon is the Mediterranean icon. The Mediterranean is not a sea.

To say “The Mediterranean” now is like saying the planet. It's a culture.

Culture and art.

It's not a sea but a culture, a way of life, a tradition and an art.

[...]

Back to top |